A Heart Touching Interaction With John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck

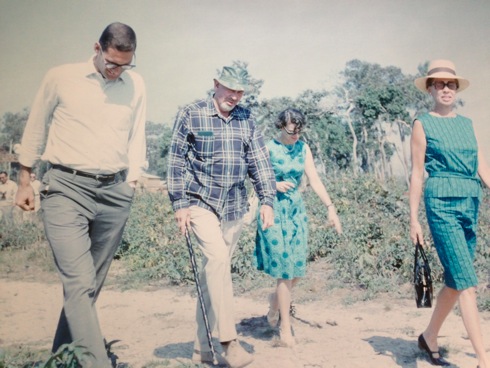

Northeast Thailand, April 1967

One lonely, frightened rooster crows loudly from under the house. It is Saturday morning, no school. There is a grey mist rising over the Mekong. Samlee, my high school principal, stops his motorcycle at the house and tells me a phuyai is visiting a village in the countryside. He is sure it is Thailand's beloved leader, King Bhumibol. I get on the motorcycle, and we take a four-hour excursion on a dusty, gutted road to the village.

Government officials, American Seabees, and local villagers wait patiently as two helicopters circle and land. The door slides open on the second helicopter. The king is not on board. I am astounded when I recognize John Steinbeck. Embassy personal and high-ranking officials escort John Steinbeck and Mrs. Steinbeck to the village square.

I don’t know why, but I immediately think about a young Henry Fonda in the movie version of The Grapes of Wrath.

Fleeing the famine and misery of the dust bowl, he is in a rickety vehicle with family and friends. An older family member dies on Route 66. They are on their way to prosperity in California.

I walk up to the Steinbeck party, introduce myself, and we talk.

We drink some, maybe too much, of the home-brewed lao-lao. Hours later, before he returns to the helicopter, I mention my desire to write.

He is cordial. He gives me some advice. He coughs, and I can smell the lao-lao. We shake hands. He returns to his wife, and they walk to the helicopter.

My principal disappears with the motorcycle. I stay overnight. It is difficult to sleep. Not because of the heat and the mosquitoes and the grass mat. It is because of the grapes of wrath.

John Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962. On this trip to the village, Mr. Steinbeck is writing articles on the Vietnam War for the Philadelphia Inquirer. Later I was informed he wrote seven concise paragraphs about me and my adventures when the Mekong flooded the region.

John Steinbeck dies a year later at the age of sixty-six.

Soon in a whirling cloud of dust, the helicopter lifts off the ground, tilts sideways, and flies in a straight line for the distant mountain. Amazed at this chance encounter, I stand there in the settling dust. Samlee walks over with a full glass of lao-lao. I am still very excited. The Seabees join us. After numerous glasses of lao-lao, the Seabees agree to come to the school and build a cement basketball court. The lieutenant guarantees it will be the first and best of its kind.

Philadelphia Inquirer

April 1967

Seabees and Peace Corps Boost Hill Villagers’ Morale

Bangkok – I’ve probably tried to tell you more about the wild northeastern provinces of Thailand than you want to know. But to me, it is important because here is the battlefront of methods and ideas, the true confrontation of our allies and ourselves with the Communist pressure of power.

And it is in places like these that we will win or lose, and the future of the world will be decided – not in Washington or Moscow or Peking, but in the rice paddy, the hill village, the fishing boat, and the conservers of the crafts of weaving and pottery, and the thousand products of the bamboo. This is the heart.

Item: In the town of Nakhon Pathom, there is a hotel and pleasure garden named The Civilized, and so it is. At the entrance to the garden where, in the evening, civilization is kept alive, there is a large sign that reads, “Girls without V.D. cards not permitted.” And inside the garden, tacked to a tree, the sad printed statement: “V.D. cards #139-#85-#62 and #18 are not valid.” How civilized can we get?

Through no fault of our own, we were booked not at the Civilized but at the Grand Hotel, a marble structure with bathrooms, each of which contains a shower, a basin, and a toilet. This is pretty grand, all right, but in the two days and nights of our occupancy, no water graced any of these luxuries. We carried buckets for the absolute necessities.

Now we have stayed in many places where there are no facilities with perfect happiness. Why is that, when surrounded with the trappings that do not work, we become furious? Elaine renamed the Grand Hotel The Uncivilized, and so we will always think of it.

Item: Lt. Dick Platt commands a small detachment of Seabees in the village of Ban Nong Chon near the river, an area that was flooded and chewed up during the terrible floods of the last rainy season when the river leaped its banks and went berserk.

The Seabees’ project is to teach the digging of deep wells to reach potable water, to teach the building of permanent bridges constructed of heavy timber, to bring some kind of medical help to people who have none.

Platt has young blue eyes and a nose which will not tan. It burns, peels, and burns again. Having the same trouble, I sympathize with him.

Not many of the units were at the base. They never are. In small squads or groups, they are out living in the villages. A project is decided on by the village. The Seabees design it, whether a bridge, a well, a schoolhouse, or water-trap latrines.

“The people do the work,” Dick Platt said. “They cut the trees, saw out the lumber, and do all of the digging and hauling. We teach them to make the forms for concrete well casings, but they mix the cement and pour it and do the digging.

“All we contribute are methods and a few things they can’t get, like nails. That building over there is the new school and meeting place. It has gone up in a week. It will be finished in another week. They won’t take a day off. It’s theirs, and they want it finished. That’s the thing. When they find out it’s theirs, and they build it themselves, you can’t stop them.”

I asked, “Well, will they be able to carry on when you pull out?”

“Sure,” he said. “We’ve got graduate well-diggers and bridge-builders working upcountry now.”

“How about the Seabees out in the villages? They must get pretty bored.”

“Well, they don’t,” he said. “They only come in when they run out of food. They’ve got too much to do to be bored.”

“How about you?” I asked.

“Me? I love it. I think maybe when my service is over, I might come back here and go it alone.”

I looked around at the wasted country, and the poor gallant attempts to survive and continue. “Why do you like it?” I asked suddenly.

Platt’s eyes began to shine. “I’ve thought about that. No rule book. We’re writing it as we go. We’re making it up. When something is needed, we do it. Same with the men out in the villages. It’s wonderful.”

And it is wonderful. It’s what every man of energy wants - to be needed and to fill the need by his work and his mind and his imagination, and in the end, to have something that wasn’t there before.

It is the dream of a creative man to be creative, whether it is interlocking those logs in the bridge there so that pressure only makes them more firm or whether it is the art of music; it is the thing a man does at his best, and it is the thing that makes him happiest. And Dick Platt put his finger on it: “No rule book.” Only us - here.

Item: Mike Fields, a Peace Corps teacher, wandered in to say hello and to pass the time of day.

“Were you here during the flood?”

“Yes. I couldn’t leave. I got a boat. People were stranded, some of them in trees. I couldn’t leave.”

“What did you eat?”

“I had eight chickens and a monkey. I was trying to raise chickens."

We ate chicken every other day. Someone ate the monkey.”

“How are you getting along?”

“Well,” said Mike, “you know how it is. When I first came, it was tough. But when the flood came, and I stayed, you know – my stock went way up.”